You’re constantly evaluating new battery suppliers, and "high energy density" is a claim everyone makes. But without knowing how to verify this crucial metric, you're making decisions in the dark.

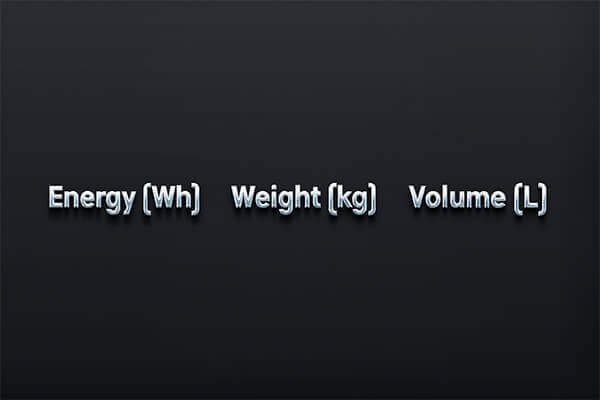

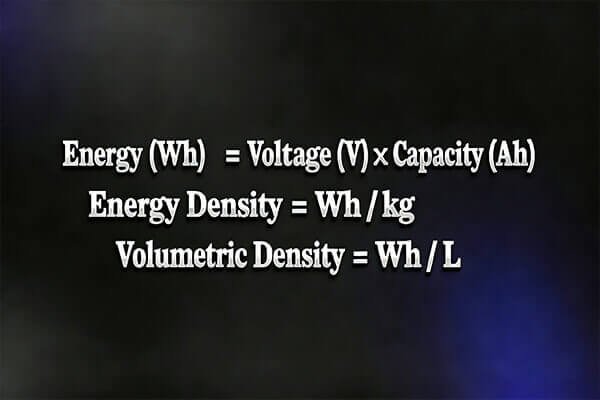

To calculate a battery's energy density, you need three key pieces of data: its total energy in Watt-hours (Wh), its weight in kilograms (kg), and its volume in liters (L). The calculation is a simple division of total energy by either weight or volume.

As a procurement manager for high-performance drones, energy density is your single most important performance indicator. It directly translates to longer flight times and heavier payload capacity. However, the term is often used loosely. Understanding the precise calculation empowers you to cut through the marketing claims and make data-driven decisions. There are two types of energy density, and both are critical for drone applications. Let’s walk through the exact steps to calculate them.

What Are the Two Types of Energy Density?

You need a battery that is both lightweight and compact to fit into a sleek drone frame. But you find that some "lightweight" batteries are bulky, while some "compact" batteries are surprisingly heavy.

The two types are gravimetric (mass) energy density, measured in Wh/kg, and volumetric energy density, measured in Wh/L. Gravimetric density tells you how light the battery is for its energy, while volumetric tells you how small it is.

For drone applications, you are in a constant battle against both weight and space. That’s why you must evaluate both metrics.

-

Gravimetric Energy Density (Wh/kg): This is the most commonly cited figure. It measures the amount of energy stored per unit of mass. A higher Wh/kg means a lighter battery for the same amount of energy, which is crucial for maximizing flight time. This is about fighting gravity.

-

Volumetric Energy Density (Wh/L): This measures the amount of energy stored per unit of volume. A higher Wh/L means a more compact battery for the same amount of energy. This is critical for designing drones with aerodynamic frames and fitting all the necessary components into a limited space. This is about efficient design.

A great drone battery must excel in both. A battery with high gravimetric density but poor volumetric density might be light but too big to fit the drone. Conversely, a compact battery that is too heavy will reduce flight efficiency.

How Do I Perform the Actual Calculation?

You have a sample battery on your desk and its spec sheet. Now you need to turn those numbers into a definitive energy density value to compare it against your current supplier's product.

First, confirm the battery's total energy in Watt-hours (Wh). Then, weigh the battery to get its mass in kilograms (kg) and measure its dimensions to calculate its volume in liters (L). Finally, apply the simple division formulas.

Let’s use one of our KKLIPO high-performance drone batteries as a real-world example.

Assumed Battery Specs:

- Nominal Voltage: 22.2V (6S)

- Capacity: 16,000 mAh (which is 16 Ah)

- Weight: 1.9 kg

- Dimensions: 200mm x 90mm x 65mm

Step 1: Calculate Total Energy (Watt-hours)

If the Wh value isn't given directly, calculate it.

- Formula: Energy (Wh) = Voltage (V) × Capacity (Ah)

- Calculation:

22.2 V × 16 Ah = 355.2 Wh

Step 2: Calculate Gravimetric Energy Density (Wh/kg)

- Formula: Gravimetric Energy Density = Total Energy (Wh) / Weight (kg)

- Calculation:

355.2 Wh / 1.9 kg = 187 Wh/kg

Step 3: Calculate Volumetric Energy Density (Wh/L)

First, find the volume and convert it to liters.

- Volume Calculation:

200mm × 90mm × 65mm = 1,170,000 mm³ - Conversion: There are 1,000,000 mm³ in a liter. So,

1,170,000 mm³ / 1,000,000 = 1.17 L - Formula: Volumetric Energy Density = Total Energy (Wh) / Volume (L)

- Calculation:

355.2 Wh / 1.17 L = 303 Wh/L

So, this KKLIPO battery has a gravimetric energy density of 187 Wh/kg and a volumetric energy density of 303 Wh/L. Now you have concrete data to compare with any other battery.

Why Is My Calculated Value Lower Than the 'Theoretical' Density?

You read reports about new battery chemistries with theoretical densities of 500 Wh/kg, but the commercial products you test are barely reaching 250 Wh/kg. This gap can be confusing and makes it hard to forecast future technology adoption.

The actual energy density of a finished battery is always much lower than the theoretical maximum because of "inactive" components like the casing, wiring, safety electronics, and separator, which add weight and volume without storing energy.

This is a critical distinction that separates laboratory science from real-world engineering. When scientists discuss theoretical density, they are often referring only to the active materials (like lithium cobalt oxide and graphite) at a chemical level. But a functional, safe, and durable battery requires many other things.

The Overhead of a Real-World Battery

Here's what adds the "dead weight" and volume that reduces the practical energy density:

- Casing: The hard shell or soft pouch that protects the battery.

- Current Collectors: Copper and aluminum foils that are essential for conducting electricity but don't store energy.

- Separator: A membrane that prevents the electrodes from touching and causing a short circuit.

- Electrolyte: The liquid medium that allows ions to flow.

- Terminals and Wiring: The external connection points and internal tabs.

- Battery Management System (BMS): For multi-cell packs, this electronic board is crucial for safety and longevity.

When you move from a single cell to a full battery pack, like those used in large drones, the system-level energy density drops even further due to the additional weight and volume of the housing, thermal management system, and structural components. As a procurement manager, you must always base your decisions on the cell-level or pack-level energy density, not the theoretical material-level claims.

Conclusion

To calculate energy density, simply divide the battery's total Watt-hours by its weight in kilograms for gravimetric density and by its volume in liters for volumetric density.